“Well, you’ve been asking about me, who I am, where I came from, how I got here. You want to know, and you’ve earned it, so have a seat, and listen to my story.”

We sit down at the table like two old buddies about to catch up. He looks up at the ceiling like his life story is carved up there, and I can tell from his look of concentration, he’s trying to figure out where to start.

He takes a deep breath, exhales, and begins. “In my senior year, 1967, I sent out college applications to UCLA, Florida State University, Northwestern. Pretty much any college that wasn’t in my home town of Plattsburgh in upstate New York. I know this will be a big surprise to you, but I was a guitar player, had long hair, smoked pot, and hitchhiked to concerts in the summer. I had a friend, Theresa, a girl I grew up with. We never went steady, that’s what we called it back then when people were considered couples. Anyway, her and her boyfriend broke up, and I wasn’t attached to anybody, so we decided to go to our Senior Prom together. I just got back from getting a tux when something came in the mail that would change the course of my future, the course of my life.

“The card bared my name along with a line of numbers—numbers I don’t remember nor do I know what they meant. I could care less about what the numbers were or their meaning. They told me I was headed to Vietnam.”

. “My father fought in World War II, and my grandfather fought in the First World War. My birthright was to go to Vietnam. When my father saw the draft card, he laughed and said, ‘Now it’s time to cut that hippie hair and make a man out of you.’

“I heard nightmares about Vietnam. Men coming home with no arms, no legs, burnt skin. Footage on the TV showed explosions and shooting helicopters. I wanted to study music, be a musician like Eric Clapton, not shoot people. I wanted a golden record, not a purple heart. I was stuck. Every college application came back as a rejection notice, and burning my draft card meant going to jail and disgracing my family line. But it’s like Bob Dylan said, ‘Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command your old road is rapidly agin.’ Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend your hand, for the times they are a-changin’.’

“As the months passed—February, March, April, May, June—it was a countdown to my expiration. At prom, I was a mummy. Zombies weren’t popular yet. During a slow dance, Theresa slugged me in the shoulder. ‘You’re being a real creep,’ she said, ‘Here I am, all pretty, and you’re thinking of what hasn’t happened yet.’

“I broke down and cried, right there in the middle of the dance floor.

“She escorted me off the dance floor. Yeah, I felt like a wimp, but that’s the last time I recall showing any real emotion. We sat at the bleachers. A couple of people saw us, luckily not enough to cause a scene. Theresa held me in her arms, assured me everything would be all right, and although she pulled me out of the despair I felt, I knew they were just words. They held weight and possibility in the gym, but the truth was that gym wasn’t where my life headed.

“Theresa had a plan after graduation. We’d leave town, her with her books, me with my guitar. We’d go out to California and join the scene out there. At the time it sounded like God spoke through her, but when I got home, and my head hit the pillow, reality struck like a hammer. I was going off to Vietnam.

“Late graduation night, I woke up from a nightmare where my father and my grandfather, both in their 20s, both dressed in their military uniforms, piled dirt on top of me while I pleaded for them to stop. All I got in return was a mouth full of dirt. When I looked down at myself, I, too, wore a military uniform, and I rested in my coffin.

“That nightmare was as vivid as my memories of prom. For a week after that, I got little sleep, and I spent hours of those sleepless nights holding my draft card over a dancing flame. One night, I burnt the corner of it. The flame chewed the corner, and I blew it out as if it were mine and Theresa’s only prom picture.

“Crazy, huh?

“So one night I came home from John McCormick’s graduation party very drunk and very stoned, and there was a roaring fire in the backyard. I ran back to check it out, and in front of the fire stood the stocky silhouette of my dad. I immediately saw fire gnawing at John, Paul George, and Ringo on the Meet the Beatles album along with the rest of my record collection. Before my eyes, my whole record collection—The Stones, The Beach Boys, Trogs—all up in smoke like some musical sacrifice to the gods.

“He held up my Loving Spoonful album and said, ‘If you can listen to this crap, you can fire a rifle.’

“I ran into the house because if I stayed out there, I was going to kill him.

“As I bolted through the house I heard him yell, ‘You will serve your country!’

“By that August, I went to Fort Benning for boot camp. In those six weeks, they brainwashed us into thinking that Communism was a virus that infected the world and how America was going to eradicate that virus. ‘You’re doing God’s will,’ the drill sergeant said once. God’s will. How the hell did he know what God wanted? I knew it was all bullshit, just propaganda, but if you hear it enough times, you believe it’s real.

“I ended up in Huay. Huay was a different planet. None of the people spoke English, and if they did, they spoke in fragments. They all sneered at us and yelled in Vietnamese. They wanted us there as much as we wanted to be there, and my 18 year-old mind just didn’t get it. Maybe I wasn’t supposed to.

“The temperatures soared at 110 degrees, and with fatigues and equipment, it felt like 1,000 degrees. I went weeks without showering, walking aimlessly through a jungle for a goal that didn’t exist. Hell, looking back on it, I wouldn’t be surprised if we walked circles in a mile radius of that jungle.

“Six months prior, I sat in a classroom learning about transversals, stressing over college applications, female attention, jam sessions, and auditions. If the future me walked into that classroom, a buzz cut under a green helmet, a bundled knapsack slung over my shoulder, and an M-16 rifle cradled in my arms, I’d think I dropped a bad tab of acid, yet there I was—sweaty, dirty, fatigued—an 18 year-old American kid in a line with others, all there because we all swallowed the political bullshit of preserving the American dream. I felt like I died and went to hell, and Theresa, prom, my days at Central Hill High School, the countless afternoons I practiced chord changes and minor scales, they were all dreams, a past life..

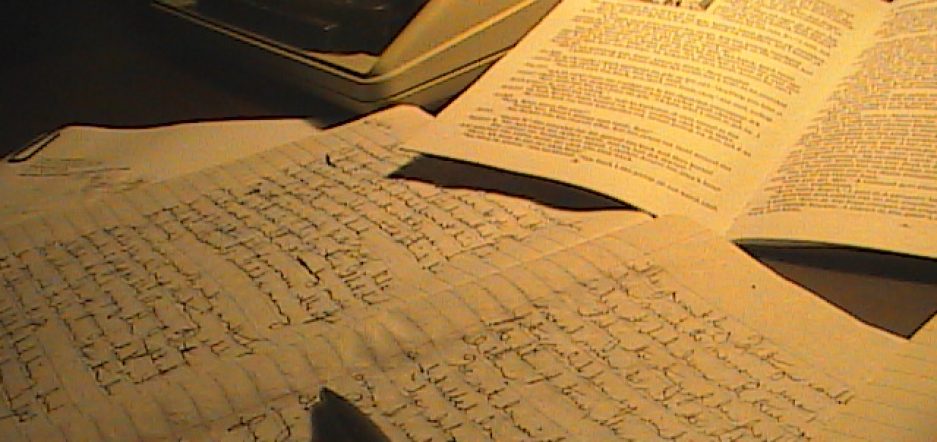

“We camped about thirteen klicks outside Tra Bong, and in war, you’d do anything to pass the time. I wrote letters to Theresa, knowing full well that she’d never get them. I had no idea what her address was. When I wasn’t writing letters, I wrote Haikus, and I made origami out of tropical leaves. Once I got a slight case of Poison Ivy on my fingertips. Believe it or not, it was the best thing to happen to me in Vietnam.

“‘Yo Edwards, you killed anyone yet?’ One of my platoon mates snickered through the darkness.

“It was most likely Gonzalez from Sacramento. Johnny Brock spoke with a Texas accent, being from Lubbock, and our Platoon leader, McGuire, hailed from New York City.

“They knew damn well I never killed anyone nor intended to. They razzed me and knew I could give two shits. That’s why they did it…because they could.”

“The next day, we passed through Tra Bong. No enemy forces, but like I said, a soldier will do anything to pass the time. And these guys, these guys had a lot of anger to dispense, and I just couldn’t relate to that. If it were up to me, we’d pass through that village with a wave and a ‘How do ya do.’ It wasn’t up to me, though. These guys pushed women, flipped tables, kicked animals. I just hung back.”

“I went into the forest like I led the platoon, but the truth was, I needed off that scene. I sat on a tree trunk sickened and distraught from the bullshit. Their cackles and screams echoed over the tree line, and for all I knew, they were raping some old Vietnamese lady. I didn’t know, and the less I knew the better. Their heckling voices got louder, and leaves and branches cracked under their boots.

“I turned around, and they stood there, shoulder to shoulder to each other like they were gonna beat the shit out of me. Compared to what happened, I wished they had.

“‘Today’s your luck day, Edwards,’ McGuire said, ‘You’re about to achieve your first kill.’

“They separated, and Gonzalez dragged a goat or a lamb, I couldn’t tell. Whatever it was, it was white and hairless with boney legs that gave out from its own weight. When it caught balance, Gonzalez kicked it in the rear, causing it to go head first into the ground.”

“McGuire pulled out his .22. ‘Kill it. That’s an order.’

“I stared at him. If I could shoot lightning out of my eyes, I would’ve shocked him.

“McGuire yanked it by the ear like a mother disciplining her child. ‘One bullet, right here.’ He thumped its head with his .22. ‘That’s it. Done. Simplest mission in Vietnam.’”

“I glimpsed at the creature, its beady eyes, slit of a mouth, and for some reason, I saw my childhood dog, Pineapple. Why? I guess it’s because you replace sights and sounds of things you don’t understand with sights and sounds of home. I didn’t want to look at the fucking thing. I didn’t want to look at anything. In my head, I played a montage of Beatles songs, but the thought cut out like one of those dickheads pulled the plug.

“‘We ain’t got all day, asshole,’ Brock yelled.

“‘Get it over with,’ McGuire said.

“I stared him down.

“Anger exploded in his eyes, and his lips curled downwards, exposing his gritting teeth. He flipped the gun and pointed it to my head.

“He cocked the hammer back, and I honestly thought, ‘Good, pull the trigger. Turn out the lights.’

“I stood up, the barrel of the gun never leaving my sights, and I walked away. I expected a bullet to the back of my head, and again I thought, ‘Go for it.’

“Warm droplets to the back of my neck and elbows followed the deafening bang. I also felt the droplets pelt the back of my shirt, way too syrupy to be drops of water. The guys walked passed me, bumping my shoulder, chuckling, muttering ‘pussy’ and ‘hippie’ under their breaths, and someone spit on my boot. The guys gathered in front of me and closed in. I knew what they did, but that didn’t mean I had to look.

“‘Check out your handy work,’ McGuire nudged me once then pushed me.

“He gripped me by the shirt, swung me around, and knocked me to my knees. Upon turning and dropping, I snapped my eyes shut from the carnage on the other side of my eyelids. McGuire’s open palm pressed against my head, pushing me down. With my eyes closed, all I saw was the orange film of the sun blazing through my eyelids, but the overwhelming stench of what could’ve passed as five skunks’ worth of spray gave me an idea of the damage done.

“I looked down at the dead thing. Its brains spilled out of the top of its head while its eye stared up into the heavens, and its tongue hung out of its mouth.”

“‘How’s it feel to be a killer, Edwards?’ McGuire asked.

“I looked down at it and believed I really did kill it. I hated Vietnam.